Upon entering the world of The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, you’re dropped into the well worn shoes of the dashing Geralt of Rivia’s with the daunting task of not only slaying every monster across the map, but more importantly finding your estranged adopted daughter, Ciri. The game itself, I must admit, wasn’t on my list of ‘games I need to play’, as I was pre-occupied with Dragon Age: Inquisition. However, watching my husband play through The Witcher I was taken aback by not only the astounding role playing mechanics, the beauty of the world, the horse mechanics (finally, someone WATCHED a horse before animating it! I know I know… quadruped movement is hard…), but once he arrived in Skellige (the game’s island nation of ‘barbarians’), I knew I had to play it. After all, how could I ignore a game that so obviously did research into what Vikings wore across all of northern Europe? This may be exciting to me because I had just finished my Master’s degree on Vikings… But nonetheless, CD Projekt Red has impressed me. So, without any further ado, here are some of the most striking images of historical representation in Skellige, and why it’s important.

First and foremost, lets talk about the female garb within Skellige. As this is one of my favorite topics in Viking Archaeology, I’ll get this out of the way first. Lets go from head to toe, shall we?

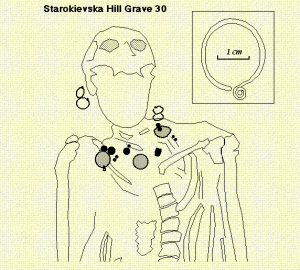

Head dresses you will see women adorning while riding Roach throughout Skellige vary widely, but one of the most recognizable are the temple rings worn on either side of the head. These are not just silly game costumes that CD Projekt Red conjured up, they actually do exist, and were worn by the Rus, Slav, and Baltic Vikings. Such examples were excavated from Starokievksa Hill Grave 30 and are found between 900 AD and 1200 AD predominately. These temple rings vary in style, precious metal, and would have obviously displayed a woman’s wealth openly, as well as held tribal importance on marriage status, familial status, and regional ties.

Another easily recognizable artifact that appears in Witcher is the Dublin/Jorvik hood. These hoods range from silk to wool, depending on the archaeological site, but it’s a simple squared hood with drawstrings. That being said, these hoods are not associated with Scandinavia – but with the Netherlands, and the UK, so regional representation is displayed throughout the game – and often combined. Often female NPC’s will be sporting a Dublin Hood with temple rings, something that most likely wouldn’t have been found in the real Viking Age, but are real artifacts nonetheless.

Further down the body we run into the brooches on a woman’s apron dress. These are very common throughout the Viking Age, as well as throughout Skellige. From Norwegian oval brooches, to Saxon-influenced circle brooches, many are represented throughout the game. Brooches served a practical purpose – holding the apron dress together – but also served as pins for beaded jewelry, a wealth status. This is displayed in The Witcher especially with the wealthier women in Skellige, such as the Jarl’s conniving widow, Birna.

Aside from brooches and apron dresses, tablet weaving is represented here with patterns that were actually in use during the Viking Age. Tablet weaving (one of my favorite past times), is an ancient form of weaving using cards – or tablets – turning to create intricate patterns. This weaving style typically just produces a strap – not bolts of cloth. These straps were then used as decorative hem. Such decorations were used to border the apron dress, cuffs, necklines, etc. These decorative hems are seen throughout the world of The Witcher but become increasingly prevalent in Skellige.

Shoes! Even the shoes adorned successfully flesh out the world of The Witcher, with many representing the Staraya Ladoga shoes.

Alright, enough with the clothes – how about the ritual slaughter of the horse right on the harbor? Its head is cut clean off – a ritual common in the Viking Age and performed for many reasons. If you stick around and listen to the NPCs around the slaughtered horse, you’ll see they’re sacrificing it for a specific reason! (Note: this is right on the harbor where the New Port inn is and where the funeral took place). This is also seen in the funerary rites right as you get to Skellige. Female sacrifice, livestock ritually slaughtered at the end of the boat, shield placed over the body, goods placed about the deceased… sound familiar?

What about the art? The ring-chain motif can be seen throughout Skellige – a motif taken straight from the Borre Style attributed to Gaut, a Viking who signed his work on the Isle of Man during the Viking Age. Not only does the ring-chain motif appear widely, so does the Ringerike art style – especially on the tapestries and house carvings throughout Skellige.

So you might be thinking, ‘Well of course they included such things, its an eastern European game studio…’ or ‘Okay, so they did their research in order to flesh out the world… so?’. Those are valid questions… and let me explain why, as a Viking archaeologist, I am so excited by it, and why I find it so important:

1: This creates jobs for trained archaeologists and historians. Being on the inside I cant count how many times I thought to myself, ‘I studied all of this, but what does it matter? I cant get a job that actually uses it.’ Not only is this frustrating, but it deters people from studying some pretty obscure subjects rather than going into business or engineering (jobs that are more secure in the USA where I am now). Having this kind of research in an industry that is more successful than film opens up jobs that deviate from just Cultural Resource Management, teaching, or research, all of which are highly insecure. This allows people to use their degree for something that millions of people will benefit from, and learn from while enjoying entertainment. Which brings me to number 2.

2: Most people wont be playing The Witcher just to see some historical and archaeological representation, and I wouldn’t expect them to. They’re playing it because its great entertainment. However, it has started to energize interest in the Baltic myths, legends, archaeology, history, and so forth. The Witcher just might do for Eastern Viking Archaeology what Skyrim did for Vikings in general. Media representation. That might not seem like a big deal, but history and archaeology thrives off demand for knowledge. If people don’t want to know what happened to the Baltic in its history, there will be no demand for research. This stretches beyond the Baltic itself, and is only beneficial. I cant count the times I’ve been playing and had to look up certain myths and legends – which only increases my knowledge of a people, of an area. Which brings me to number 3.

3: The more knowledge about a geographic region or people is spread, the more tolerance and empathy it creates. Now, I am not saying that the one culture who could benefit from being understood is the enormous Baltic/Scandinavian region – as most western people know and love the Vikings anyway. What I am saying is that video games can serve as a great vessel for gateway knowledge about an area. What would the western world learn from having a game akin to The Witcher or Skyrim but placed in the viewpoint of a Syrian? An Afghani? A Nigerian? A Native American? Or someone who’s gay (like the wonderful storyline from Dorian in Dragon Age: Inquisition)? It can serve to open peoples minds, play on empathy, a thirst for knowledge, a stimulation for curiosity, and ultimately compassion – all through a from of entertainment. Propaganda? I don’t see it that way. I see it as entertainment that for once, isn’t mindless.

Image Links/Sources:

http://members.ozemail.com.au/~chrisandpeter/trmain/tr1main.html

http://forum.kaup.ru/viewtopic.php?f=9&t=50

http://www.revivalclothing.com/images/view.aspx?productId=2057

http://vikingdrakt.blogg.no/1239973865_drakter_fra_de_siste_.html

http://game-maps.com/Witcher3/NPC-BIRNA.asp

http://rukomysli.livejournal.com/?skip=60&tag=%D0%BE%D0%B1%D1%83%D0%B2%D1%8C

http://blog.britishmuseum.org/2014/04/16/the-viking-way-of-death/